Author: Tatjana Koprivica

A big turning point in European art happened between 1905 and 1910, i.e. amid the Autumn Salon of fauvists, the emergence of the art group Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Wassily Kandinsky’s first abstract canvass.

However, the most revolutionary piece of art in the history of the modern movement from early XX century was Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), which introduced cubism (1).

The beginning of the XX century brought great scientific advances in physics, chemistry, biology, astronomy.

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity (1905) established a new understanding of the structure of space, which was an elastic and movable multi-dimensional structure, bended to the extent to which other forces were acting on it.

The painting was no longer a renaissance “window into the worldâ€, it no longer transfered the visible, but explored the very phenomenon of watching, which put the artist into a dynamic position.

The artist entered the painting’s space, which had been a forbidden territory for him/her for centuries, and destroyed the old ways of artistic thinking (2). The cubist works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque marked the beginning of the “dissolution†of paintings.

In a manifesto announced by poet Tommaso Marinetti in 1909, futurism rejected the old world, tradition and civil institutions.

“We have to destroy libraries and museums which are covering Italy like a cemetery; we need to live a new, modern life which is ahead and which is dominated by only one beauty – speedâ€, Marinetti wrote (3).

In the years that followed, the non-objective art of Kandinsky, Malevich and Mondrian showed, for the first time in the history of European painting, that painting could exist objectless, reduced to the forces which produced it, independent from the external reality and mimetic methods (4).

- Tableau I *oil on canvas *103 x 100 cm *signed b.r.: P M 21

The most important European art centers were Paris and Munich, with Dresden, Berlin and Moscow becoming increasingly significant.

While the most progressive powers in European art were denying traditional art and traditional civil institutions, such institutions in Montenegro could have been only an ideal towards which it was moving slowly.

One of the prerequisites for the main energy to be pointed in this direction was the dissolution of the political map of the Balkans, where the presence of two major empires hindered any development, including the one in culture and art. This process reached its peak in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913).

According to the well-known practice where Montenegro becomes interesting to the European public, i.e. European media only in the times of war and great crises, European magazines published during the Balkan Wars news and “images†from Montenegro.

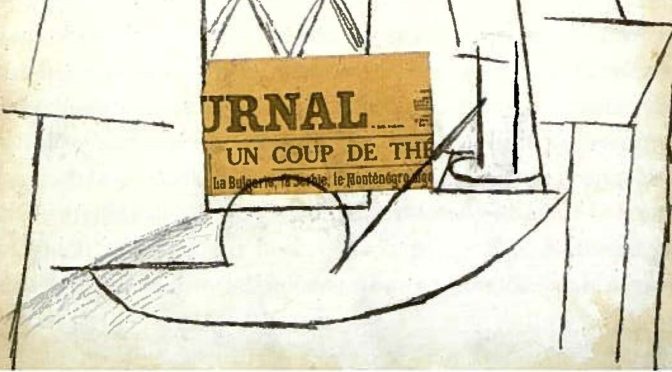

Even though cubism had not reached Montenegro, Montenegro reached cubist paintings.

In 1912, Picasso transferred fragments of these stories on Montenegro published at covers of French journals onto his collages (5).

The Balkan Wars were a horrid introduction into the First World War (1914), by the time, the most destructive armed conflict in Europe’s history.

While, in 1917, Europe was being devastated by the winds of war, Dadaists were creating anti-art, Theo Van Doesburg De Stijl, Marcel Duchamp calling R. Mutt’s Urinal a piece of art (readymade), while the October artists were severing all bonds with the old art world and were building a new one.

The end of WWI brought recomposition of Europe. Major empires were taken down: the Habsburg, the Russian, the German and the Ottoman, and new states emerged on their ruins.

Montenegro disappeared as a state. Although the war operations ended in November 1918, the peace agreements on which the new European order was based were drafted at international conferences from 1919 (the Versailles Conference) to 1923 (the Conference of Lausanne) (6).

Even in such circumstances, muses were not silent. They were just somewhat quieter.

The October Art

The Revolution in October 1917 was welcomed by avant-garde artists as a futuristic dream on industrialization, machine, war and the great dynamism coming true.

“The Art of Propaganda†was the leading idea in the first four years of the heroic communism. The life in Russian streets had never been as exhuberant.

Recitals, rallies, the painting of houses and trees, concerts at city squares, public games, trials against national enemies and open-air theater plays were every-day forms of communication in which the masses participated.

Artists mocked the church and deposed bourgeoisie, glorified the Soviet justice, educated the public in various fields (7).The old world was crumbling down and with it the “old†art.

In 1918 in Petrograd (St. Petersburg), on the occasion of the first anniversary of the October Revolution, Nathan Altman decorated a square by setting up a futuristic construction underneath an obelisk, covering all walls with cubist and futurist paintings.

Two years later, in 1920, during a celebration in Petrograd, directed by Dimitri Tiomkin, Altman, Puni and Boguslavska, a true attack by the army and people was carried out against the Winter Palace (8).

Drawing a clear line between the old and the new art was very important. Lunacharsky, as People’s Commissar of Education and Culture, established the Department of Visual Arts (IZO). In November 1918, a number of discussions titled Sanctuary or Factory were held at the Winter Palace.

At one of these discussions, Mayakowsky said: “We do not need a mausoleum for art, where dead works can be worshipped, but rather living factories of the human spirit – in the streets, in the tramways, in the factories, in the workshops and in apartments of the working class†(9).

Propaganda ships (Red Star) and trains (Red Cossack) took books, pictures, newspapers and agitators to frontlines and remote parts of Russia.

The three basic tasks of the avant-garde artists were to defend revolution, to develop art as a vital human need all across the vast Russian land and to turn ordinary man into an active participant in creation (10).

Avant-garde was convinced that “art was not the privilege of the elite and isolated individuals; art was life and event, it belonged to all and differences between people must be lost in it†(11).

In 1918, Lenin’s government allocated 2,000,000 rubles for the purchase of art pieces, so from 1918 until 1921, 36 museums and galleries were established all over Russia (12).

Russia was the first country in the world which officially exhibited abstract art.

Old Academies were abolished and new ones were opened in Petrograd and Moscow – SVOMAS and VKHUTEMAS.

Students lived in free communities and chose their professors. Anybody could attend the Academies, regardless of their level of previous education. Professors at the Academies were Kandinsky, Malevich, Tatlin, Altman, Pevsner, Rozanova, Udalzowa, Punin, Sternberg and others.

In 1919, Malevich established the school of UNOVIS (the Affirmers of the New Art) in Vitebsk.

Due to anarchy, the Academy in Petrograd was soon shut down and was reorganized in 1921 (13).

IZO was abolished in 1921. Artists of the “left tendencies†gathered around the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK).

The first INKhUK’s program was written by Kandinsky as a synthesis of suprematism, constructivism and his own theories.

Two left wings would soon form, whose conflict was: spiritual or industrial, i.e. laboratory or productive art?

Laboratory art implied suprematism and abstraction in Kandinsky’s style. This tendency was especially promoted at the Tenth State Exhibition: Non-Objective Creation as Suprematism (1919).

At this exhibition, Malevich exhibited the White Square on White and Rodchenko Black on Black.

Another tendency, the productivistic, was headed by Vladimir Tatlin, who believed that artist is not a philosopher moving through metaphysical worlds, but an architect who merges the material with the intellectual.

In 1920, Tatlin designed the Monument to the Third International. (14). Even though it was never constructed (only a model made from wood and metal was exhibited), the Monument to the Third International is considered the first modern monument in the history of European art.

Constructivist ideas were further developed by Alexander Rodchenko and especially important was the Realist Manifesto published in 1920 by Naum Gabo and Antoine Pavsner (15). The idea of productive art won, so Kandinsky, Gabo and Pevsner left Russia.

In the time of the New Economic Policy, Proletkult called for cooperation between industry and art as “a path and the future†of the art of proletariat.

Proletkult defended these ideas until its abolishment (16).

While the division between left-wing October artists grew, a “right wing†emerged in 1922, gathered around the association AKhRR (Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia).

In their resolution, they stated: “We will depict the present day: the life of the Red Army, the workers, the peasantry, the leaders of the revolution and heroes of labor. We will give the true picture of events and not abstract concoctions discrediting our revolution before the international proletariat” (17).

This association got more and more followers, especially since Kandinsky, Chagall, Burljuk, Jawlensky, Pevsner and Gabo left Russia, Rozanova died and Malevich and Tatlin withdrew.

In 1932, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) adopted the decision On Restructuring Literary-Artistic Organizations, which ended avant-garde and laid the cornerstone for the socialist realism which was to become the official ideology in USSR culture.

Even though October did not have its official art, based on the essence of its idea, it took the side of anything free and progressive.

This was its exceptional contribution to the modern European art (18).

The art of the Russian avant-garde had a huge influence on the movements in the European art in the twenties and thirties of the 20th century. Kandinsky, Chagall, Gabo, Pevsner, Jawlenski, Burljuk, Larionov, Goncharova and others continued their artistic work in the countries of the Western Europe.

(First part)

[1] D. Eimert, G. Apollinaire, Cubism, Parkstone Press 2010, 47-48.

[2] L. Trifunović, Slikarski pravci XX veka, Belgrade 1994, 53-54.

[3] Id., op. cit., 58.

[4] L. Trifunović, op. cit., 72.

[5] T. Koprivica, Balkanske inspiracije Pabla Pikasa, Inflight 10, 43-44.

[6] Around 18,000,000 people died in the war, while around 23,000,000 were wounded.Â

[7] L. Trifunović, op. cit., 78-79.

[8] L. Trifunović, Umetnost oktobra, in: Studije, ogledi, kritike, IV, ed. D. Bulatović, Belgrade 1990, 87.

[9] L. Trifunović, Slikarski pravci XX veka, 79.

[10] Id., op. cit., 79-80.

[11] L. Trifunović, op. cit., 79.

[12] Museums are divided in three groups: display museums, historic museums and art culture museums; L. Trifunović, Slikarski pravci XX veka, 79.

[13] L. Trifunović, Umetnost oktobra, 87.

[14] Tatlin’s idea was a glass cylinder which would spin around its axis once a year and which would serve as a space for lectures and public activities, and a square which would spin around its axis once a day and which would house an information center which would publish bulletins and manifestos and which would inform the whole Moscow through its spokesperson.

[15] S. MijuÅ¡ković, Od samodovoljnosti do smrti slikarstva. UmetniÄke teorije (i prakse) ruske avangarde, Belgrade, author’s electronic edition, 150-154.

[16L. Trifunović, Umjetnost oktobra, 90.

[17] Id. op. cit., 91.

[18] L. Trifunović, Umjetnost oktobra, 93.