The NikÅ¡ić local elections taking place to elect municipal office-holders for the next four-year term were dubbed “D-Day”, a crucial day for deciding on the safety and life of NikÅ¡ić men and women, as well as of all Montenegrin citizens.

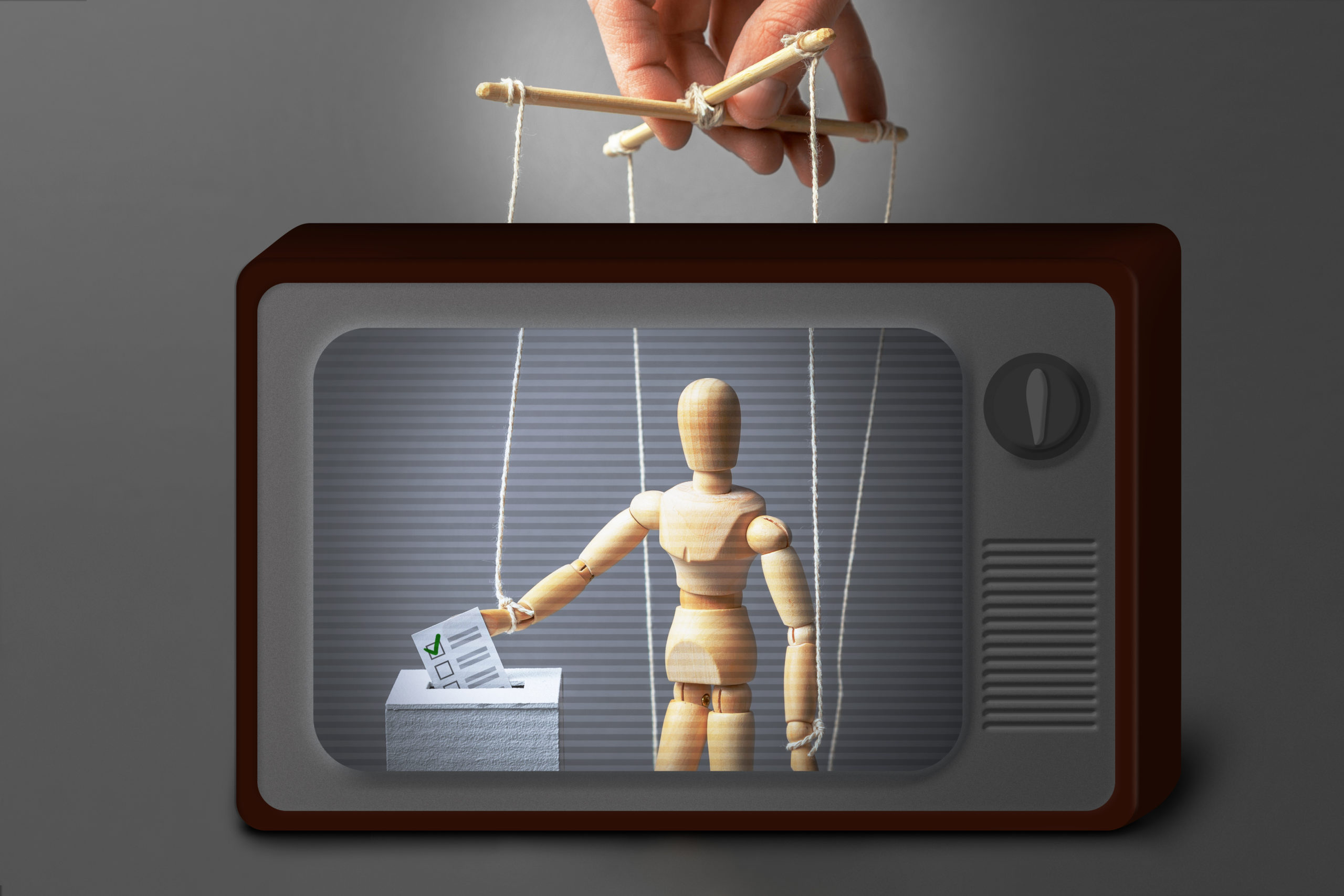

Both external and internal actors were creating the “to be or not to be” atmosphere through public space, social networks and media.

Disinformation flow that overwhelmed public space was more intense than in the parliamentary elections held in August, and raising tensions in the entire society was the “normal” feature of election campaign.

Local media were informing the public about attacks on individuals for carrying national symbols, without citing concrete evidence. After the police would deny the political and national background of the incidents, the media would put an end to those allegations, without further explaining to the public what really happened.

Meanwhile, tabloids from the neighboring countries were citing unnamed sources and “anonymous sources whose identity is known to senior editors,” warning of incidents that were yet to take place, which, as usual, did not occur. Reports on individual incidents were biased, depending on which side the editorial staff was favoring.

According to the established matrix, the media ran headlong into a smear campaign against candidates in the election, engaging in speculations about individuals’ health issues and plying the public with lies imported from social media that were otherwise easily verifiable.

Raskrinkavanje uncovered false claims made on social media that would end up on front pages of web portals without any prior fact-checking. Footages made before and during the election day, containing almost no evidential value, were used to fuel accusations of vote buying, “seizing” a ballot box and to further stir up the atmosphere.

Serbia-based tabloids were consecutively publishing identical articles full of false claims, with only a couple of minutes apart, which might serve as a signal of a coordinated action.

Again, we witnessed the re-emerging of “one-off” pre-election web portals, which were active during the parliamentary election campaign. They were posting copious disinformation that were then spread through other disinformation channels, all the while citing “reports published by Montenegrin media.”

Majority of media outlets reported on violation of anti-COVID measures on the same principle – if we support those who violate the rules, it doesn’t matter if they are wrong. Rallies staged by opponents would make it to web portals’ front pages, labelling them risks to public health, whereas violations of measures by those backed by a media outlet would get swept under a rug or completely ignored.

Religious procession vehicle convoys and patriotic car convoys, an authentic product of Montenegrin society, have been described either as “magnificent” and appropriate or as a threat to health and a provocation, depending on which media was doing the coverage.

Another peculiarity of the NikÅ¡ić elections was that they were turned into the “clash of flags” instead of clash between different election programs offered to voters. Apart from TV debates, where election programs were also sidelined, citizens were almost completely deprived of hearing about concrete intentions for NikÅ¡ić and steps meant to solve problems at the local level.

Political parties also showed lack of responsibility by dishing out false allegations about physical conflicts and stating publicly that they would “take matters into their own hands”.

All of the above clearly indicates that elections in Montenegro are increasingly looking like western movies rather than a democratic process, and domestic and foreign actors play a major role in this.

Alongside the necessary normalization of elections, where citizens are offered solutions for water supply, sewerage, streets paving, renovation of parks instead of merely being given the choice between a green, red or tricolor flag, the state must seriously attend to disinformation during the election process.

Montenegro still lacks a clear strategy to combat disinformation carried by both local and regional media, as it is the citizens that ultimately pay the price for such reporting and the chaotic situation it causes.

Editor in chief of Raskrinkavanje.me portal

Darvin Murić